European Central: No, The Dutch Didn’t End The Far Right. But They Threw A Mean Left Hook

The Associated Press

For many pundits and analysts, the recent Dutch election came as both a surprise and a bellwether. It was nail-bitingly close, and when all the votes were tallied, the liberal-progressive D66 party stood a couple thousand votes stronger than the far-right Party for Freedom (PVV).

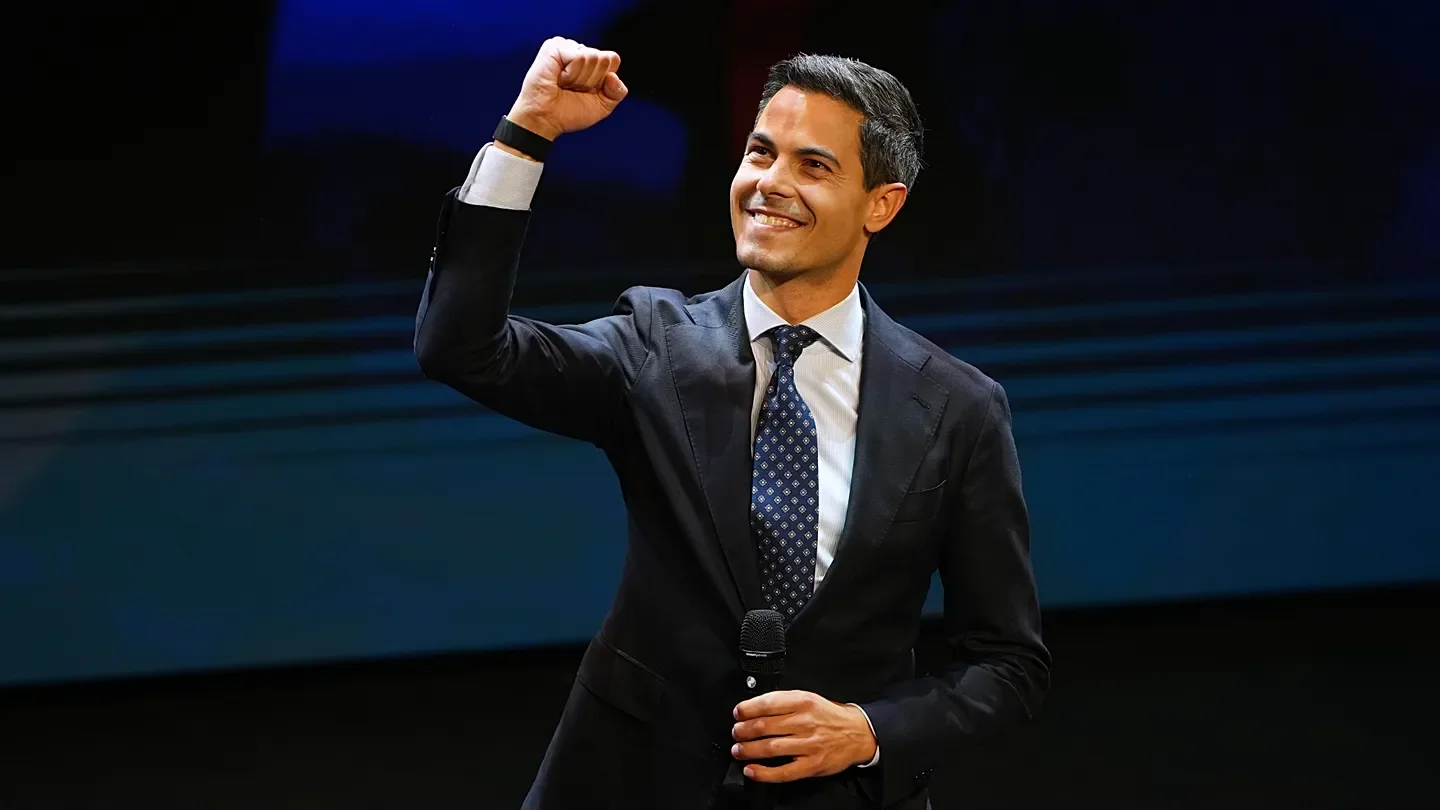

Rob Jetten, D66’s leader, is poised to become the youngest and first openly gay Dutch prime minister, if he can successfully form a coalition. But far more attention is being paid to the fact that a far-right party has been voted out of power, which stands out as an anomaly in comparison to the rest of Europe’s far-right parties being on the rise.

With a uniquely positive “Yes, we can” slogan, Jetten weaponized hope and the desire for stability alongside a savvy use of social media to surge in the final weeks. But there are also failures of the PVV that explain their relative downfall. The coming months and years will be crucial for the PVV and Jetten, and depending on how coalition talks play out, the Dutch election could show a glimpse of what is in store for far-right parties should they fail.

A Chapter Of Chaos, Closed

One of the PVV’s key failures has been the sheer political chaos that engulfed their time in power. This election was the third in five years, after the PVV collapsed their governing coalition back in June after a mere year in power. Geert Wilders, the PVV’s leader, withdrew his party after his failed push for 10 additional asylum measures, including a freeze on applications and limiting family reunification.

The move immediately drew ire and exasperation from many, including the then prime minister, Dick Schoof, who called the move “irresponsible and unnecessary”. But this chaos wasn’t new to Dutch voters: Since their shock 2023 victory made them the largest party, the PVV had presided over an era of political chaos.

The PVV’s coalition consisted of the PVV, the conservative-liberal VVD, the Farmers' Citizen Movement, and the centrist New Social Contract. Each party had differing views on myriad issues, and during its 11 months at the head of the European Union's fifth-largest economy, most policies ran into legal, logistical, or political roadblocks.

One of the key drivers of the PVV’s electoral success was, as it is for many far-right parties in Europe, immigration. But infighting and political crises always kept robust asylum legislation stalled, and as a housing crisis created a 400,000 home shortage, support for Wilders and the PVV slowly seeped away.

That is not to say that the PVV truly “lost” this election by any means. Despite most mainstream parties ruling out governing with Wilders, his party still won 26 seats, tying Jetten’s D66 party. Despite still having parliamentary weight, though, they seem to be locked out of true governing power. While some of that is due to backlash over their time in government, some of it can be attributed to a resurgent D66.

Dutch Politics “Respectful And On-Topic” Once Again

There are three main reasons that Jetten won, the first being exhaustion with the infighting-riddled PVV and its lack of success. The second has much more to do with Jetten himself.

Many have likened Jetten and his campaign to that of former U.S. President Barack Obama’s. An upbeat slogan (Jetten’s “Het kan wel” translates to “It can be done” or “Yes we can”, the latter of which was Obama’s slogan that originated with labor activist Dolores Huerta) combined with a charismatic figure, which also has echoes of Obama.

This optimism was paired with an indomitable smile that appealed to a nation seeking a sense of stability after the PVV’s tenure, and a savvy media campaign. Over the final months of the election, Jetten and his team crafted a series of appearances that won many voters over.

Jetten capitalized on TikTok’s reach, he was featured in a broadcast news segment about his love story with his fiancé, and he even placed third in the final part of a trivia game show called “The Smartest Person.” Furthermore, Jetten drank beers with far-right voters, a welcome sight in polarized times.

It also didn’t hurt that before 2023, the Netherlands was considered a bastion of liberal social ideas, something that runs in contrast to much of the PVV’s rhetoric. The PVV rose despite this in large part due to rising Islamophobia and anti-migrant sentiments, alongside strategic voting. But what perhaps sealed the deal for Jetten this time around were his policy aims. On top of his optimism and the exhausted voter base, he gave concrete plans for the issues facing the Netherlands.

On the housing front, he backed a plan to build 10 new cities and reduce red tape around re-districting and home sharing. He remained a huge proponent of green energy, a mainstay policy of his party, alongside backing higher education as well.

Right now, however, the main political issue in Europe is immigration, and he appealed to voters across the spectrum with a strict, but humane and thought-out approach. Jetten’s D66 says that people should apply for asylum while they are still outside the European Union, instead of being allowed to apply once they have arrived in the Netherlands. In addition, they back removing migrants who committed crimes from the country.

The feasibility of these programs remains uncertain, but their appeal as concrete proposals as opposed to just rhetoric is undeniable.

Canary In The Dutch Canals

Many onlookers hailed this election result as a shining example of how to beat populist movements; Jetten himself said that his party had “shown to the rest of Europe and the world that it is possible to beat the populist movements if you campaign with a positive message”.

But the country is still sharply divided, and while there are lessons for neighbors to learn, there are also Netherlands-specific circumstances at play.

Despite being seen as a progressive nation, the support for Dutch far-right parties is undeniable, especially when compared with modest showing of the sizable but sidelined left-wing parties.

Additionally, while the PVV didn’t win big, other far-right parties gained strength. Wilders lost 11 seats compared to 2023, but the far-right Forum for Democracy won four, while the hard-right JA21 party gained nine seats. Some of this gain was due to voters switching from PVV and Wilders to similar parties, and now the far-right combined now has 42 seats in the Dutch parliament, representing over a quarter of the votes.

Nevertheless, for parties looking to subdue the far-right, there are lessons. In New York there was another victor eerily similar to Jetten, with progressive policies and an air of hope: Zohran Mamdani. When concrete issues meet hope for a better future, these elections seem to be showing that there is a global voter base craving that combination.

Both campaigns benefited from weaker opponents, with Wilders’ hyper-centralized party structure and infighting mirroring Andrew Cuomo’s scandal-ridden career, so should the far-right mount a proper challenge, then good vibes and hopes might not be enough.

But the Dutch still showed what happens when the far-right doesn’t live up to the hype, and potentially what happens when they also fail to address the complex problems facing European leaders. So while the far-right in the Netherlands hasn’t been ended by any means, it was just hit with a mean left hook by a liberal-progressive promising a better future. It seems, at least for the moment, that “hope, not hate” politics goes a long way nowadays.